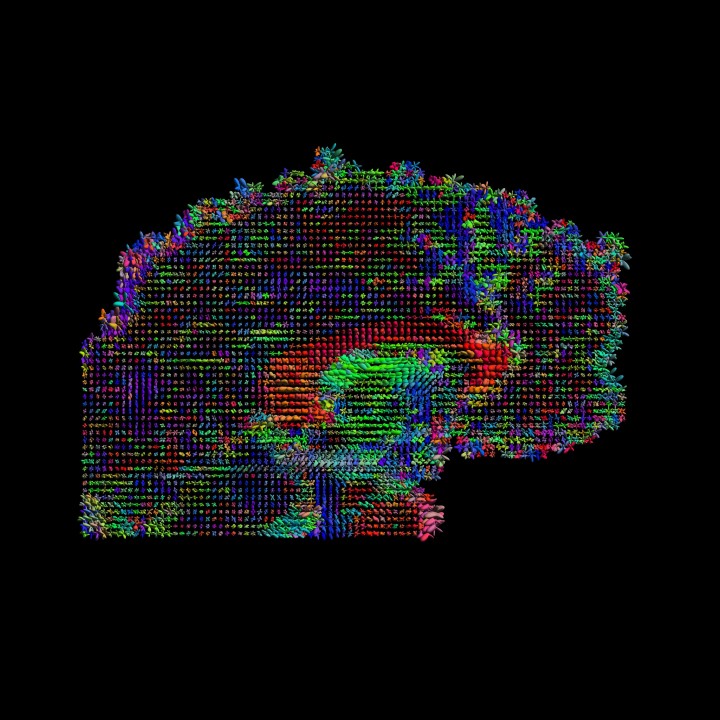

New techniques and technologies of big data are helping researchers better understand the brain. In this study, a Penn State team studied data from the Human Connectome Project to better understand the correlations between brain features, such as cortical thickness and connectivity, and various behaviors. IMAGE: BY DAVID SHATTUCK AND PAUL M. THOMPSON

Brain thickness and connectivity, not just location, correlates with behavior

Posted on July 22, 2020UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Most people think of the brain as divided into regions that are each responsible for different functions, such as language and fine motor skills. A new study by Penn State researchers suggests that there’s more to the story: The thickness of the brain’s tissue and a brain region’s connectivity may play an equally important role in linking brain and behavior.

In a study, the researchers, using data gathered by the latest neural imaging technology, found that both a specific spatial pattern of cortical thickness and functional connectivity was significantly correlated with certain behaviors. Cortical thickness refers to the depth of the outer layer of neural tissues in the brain’s cerebrum in charge of neural computing. Functional connectivity describes how connected the regions of the brain are with each other. Connectivity can refer to connections between individual neurons, groups of neurons, or other brain regions.

According to Xiao Liu, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and a co-hire of the Institute for Computational and Data Sciences, neuroscience has long recognized the connection between specific regions of the brain and certain behaviors.

“It’s been an essential idea in modern neural imaging that different regions of the brain are in charge of different functions,” Liu said. “For example, we know what part of the brain is in charge of processing visual information, or that some regions of the brain are more in charge of those higher order cognitive functions. That represents the traditional neural imaging studies, which try to map brain function.”

However, mere brain location failed to completely explain all of the connections between brain location and behaviors, he added.

The researchers said that cortical thickness and the connectivity contrast between brain regions — more specially between the low-order regions in charge of simple sensory and perception functions and the high-order areas responsible for high-level cognitive tasks — could better explain correlations with positive behaviors, such as how a person performs on memory and cognitive tests, their sense of life satisfaction, and educational attainment. Similarly, these features correlated with negative behaviors, including substance use, rule-breaking behavior and anger. This spatial contrast pattern is consistent between the cortical thickness and functional connectivity measurements even though they represent distinct structural and functional information of the brain.

Liu said that exploring these brain features could not have been accomplished without new techniques and technologies of big data. In this case, the Human Connectome Project (HCP) used the latest technology to collect brain images, including functional magnetic resonance imaging — or fMRI — data and structural brain imaging, and incorporated hundreds of behavioral, cognitive, psychometric and demographic measures from a large cohort of 1,200 subjects.

In this study, the researchers used data from 818 of the project’s participants who completed all four resting-state fMRI sessions, which can create images of the brain while at a resting state. To analyze the connections between brain areas, the researchers relied on fMRI technology, which measures blood flow in the brain to assess activity. The technology can give scientists the ability to watch the brain at rest, or resting state fMRI, and as it takes part in various activities. Watching the brain change over time as it engages in a variety of activities adds a whole new dimension to brain data analysis, according to the researchers, who report their findings in a recent issue of NeuroImage.

“With the functional data, we are not just collecting 3D imaging, but we’re actually collecting 4D imaging — spatial imaging along different time points,” said Liu.

For cortical thickness, the researchers examined the relationships between the cortical thickness over the entire cortex — or outer layer — of the brain and the resting-state functional connectivity among 200 distinct brain regions and also with 129 non-imaging behavioral and demographic measures.

He added that this ability to watch both the brain’s structural properties and functional connectivity is particularly important for understanding the brain’s influence on behaviors. Behavioral tests were used to collect individual differences between the participants’ intelligence, aggressive tendencies and life satisfaction. The project also gathered behavioral, cognitive, psychometric and demographic data on these subjects.

Liu worked with Feng Han Yameng Gu, a doctoral student in bioengineering; Gregory L. Brown, a doctoral student in engineering science and mechanics and Xiang Zhang, associate professor of information sciences and technology, all of Penn State.

This research is supported by the National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award.