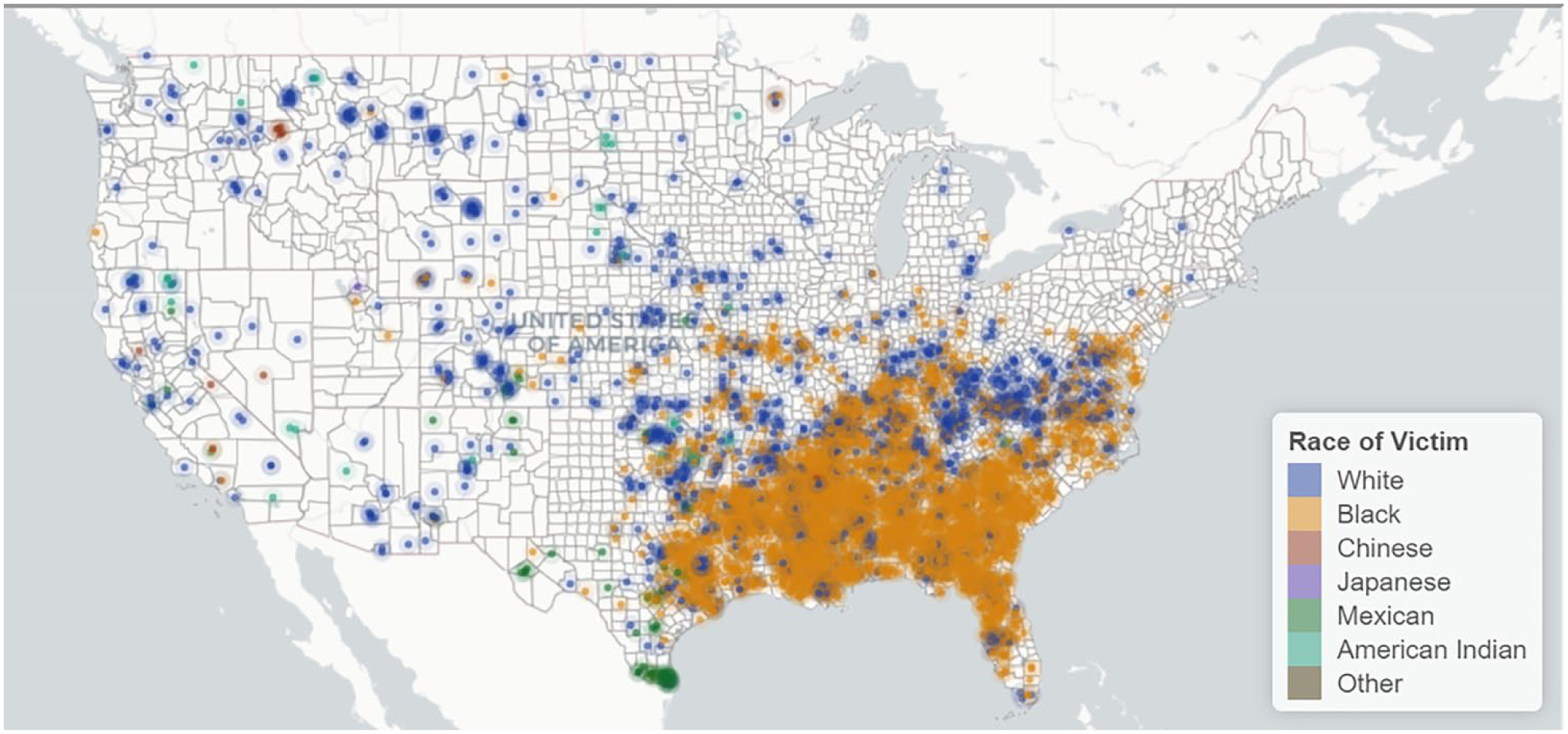

While most people tend to thinking of lynchings as something that mostly happened in the South, mob violence was widespread in the United States from 1883 to 1941, and its victims included nearly all races and ethnicities, according to researchers. An interactive map shows the extent of this particularly brutal form of violence.Image: Penn State/Charles Seguin

Map reveals that lynching extended far beyond the deep South

Posted on May 15, 2019UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — An interactive map of lynchings that occurred in the United States from 1883 to 1941 reveals not just the extent of mob violence, but also underscores how the roles of economy, topography and law enforcement infrastructure paved the way for these brutal, violent outbursts, according to researchers.

Although often thought of as unique to states in the southern U.S., lynching was practiced across the country and, although Southern blacks were by far the most common victim, the violence left few races and ethnic groups unscathed, said Charles Seguin, Penn State assistant professor of sociology and social data analytics and an affiliate of Penn State’s Institute for Computational and Data Sciences. He added that slavery and racism’s effect on this mob violence is deeply etched into the patterns of lynching displayed on the map, but lynching also occurred in Northern states, which had abolished slavery long before the Civil War.

“Although people knew about these lynchings at the time, I doubt many people today now know that brutal lynchings occurred in places like Chicago, Illinois; Duluth, Minnesota; or in Coatesville, Pennsylvania,” said Seguin. “Further, many people probably do not realize just how brutal those lynchings were. What we are showing here is a legacy of racism and vigilante violence that stretches far beyond what is commonly remembered. I think that Ida B. Wells-Barnett put it best when she said that lynching was ‘our national crime.’”

“Our National Crime”

The researchers drew on data collected by the NAACP and Chicago Tribune of lynchings that were reported in the contiguous U.S. from 1883 to 1941, as well as data from lists published by historians. Of the 4,467 people who were listed as victims of lynching, 3,265 were black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, and 38 were American Indian. The researchers confirmed the data collected by the Chicago Tribune and by the NAACP by verifying the accounts in local newspapers. They also used the newspaper accounts to estimate the mob size and determine the race and gender of the victim, alleged offense that incited the mob, and the method of murder.

According to the researchers, who report their findings in the current edition of the open access journal Socius, the victims of mob violence in the South were overwhelmingly black. This pattern of violence, however, extended to areas outside of the deep Southern states, but remained centered in areas where slavery-intensive industries — including cotton, tobacco and hemp farming — were located.

“In Missouri, for example, the map shows a cluster of black lynchings along the Missouri River, which was called Little Dixie, where slavery was prevalent in the growing of hemp and tobacco,” said Seguin. “In West Texas, also, you see another cluster of black lynchings. That marks the western edge of the cotton agriculture at that time.”

Seguin added that other cultural and economic elements of slavery served as the infrastructure of the lynching regimes in that region.

Correlation Between Slavery and Lynchings

“The almost perfect correlation between slavery and lynchings was surprising, but we’ve known that lynching was a legacy of slavery for a number of reasons,” said Seguin. “Racism, of course, is a part of that legacy, but also how slavery structured the economy, placing poor whites in competition with newly freed black people. Much of the infrastructure used to carry out lynchings was also laid out in slavery. For example, slave patrols, which were made up of private citizens who formed manhunts to find escaped slaves, later served to conduct manhunts for lynching victims.”

In the American West, victims tended to be white, although there were also black, American Indian, Mexican nationals and people of Mexican descent, and Asian victims. In this region, which includes the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico and other Western states, the lynchings appear to be connected to a lack of official law enforcement organizations in those areas, according to the researchers.

The map also shows that topography and geography may have played an underlying role in lynching patterns. For example, in the Appalachian region, geography made the land unsuitable for large scale slave-based cotton agriculture. Many of those who lived there were whites engaged in herding agriculture, which tends to produce conflict over property, and a culture that emphasized the importance of defending one’s honor — violently if necessary. Lynching victims in much of the Appalachian tended to be white as a result, said Seguin, who worked with David Rigby, doctoral candidate in sociology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The data for this study is available on the researcher’s website.

Future research may look at how certain lynching events served as a springboard for legal changes and shifts in public opinion on mob violence, said Seguin.

The National Science Foundation supported this work.